There was a time when the Andromeda Nebula was the end of the Universe. At least, a number of astronomers in the early 20th century still thought that fuzzy objects in the night sky – such as the Andromeda Nebula – were part of our Milky Way, and that our Galaxy was all there was to the Universe. Other researchers saw the nebulae as distant stellar islands, believed that the space in-between was barren and empty – and held the Universe to be considerably bigger. Observation data were unable to clear the matter up: Back then, it was not possible to measure the distance to the stars. Today, we know that the Andromeda Nebula is a separate galaxy that is 2.5 million light years away.

And today, we also have high-resolution telescopes – terrestrial and space-based models – that supply ever more precise data. Moreover, we have long since had an established model, known as the Standard Model, that describes the development of our universe. Notwithstanding, Daniel Grün, a cosmologist at LMU, has this to say: “There is something wrong with the Universe. Or at least with our idea of how it might work.”

Infinite expanses

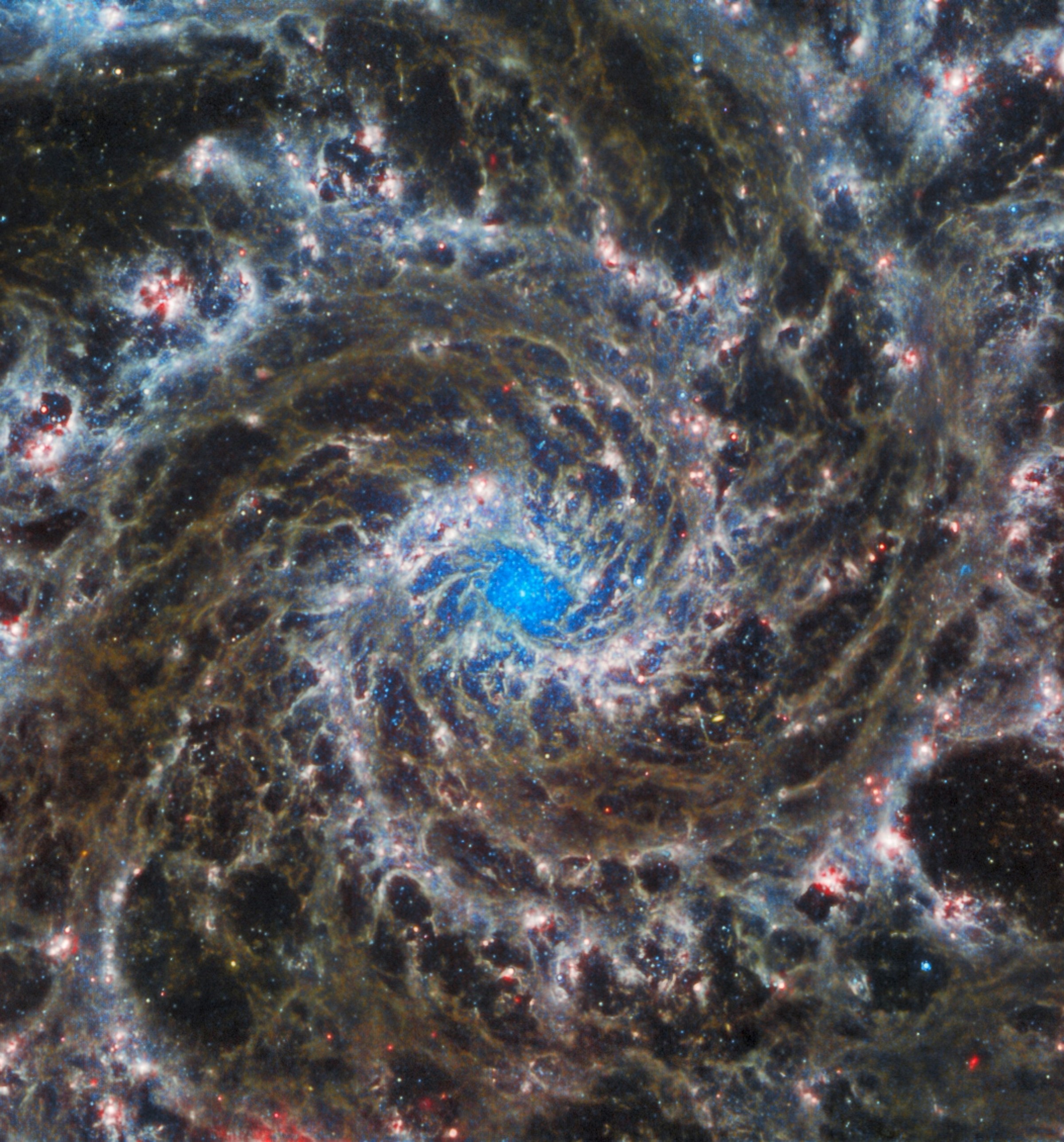

High-resolution telescopes allow us to observe the universe with ever greater precision. The James Webb Space Telescope provides fascinating images of distant galaxies, including the Phantom Galaxy shown here.

© JWST/ESA

Standard Model in the dock

Grün speaks of cracks in the foundations of cosmology, puzzles that researchers are currently addressing: It may be that the Universe today is expanding faster than it should do according to the theory. That said, the increase in the rate of expansion appears to have slowed again in the past five billion years. Nor is it clear whether today’s measurements of the matter distribution line up with the theory. “Our best explanatory model, the Standard Theory, is in the dock right now,” Grün says. Numerous LMU scientists, members of the ORIGINS Excellence Cluster, have recently gained important insights that could help us ascertain whether these cracks can be mended, or whether they are rooted in more fundamental problems with the theory.

»There is something wrong with the Universe. Or at least with our idea of how it might work.«

Daniel Grün

A good place to discuss such matters is the LMU Observatory in Munich-Bogenhausen. “It’s the first observatory in the world where spectroscopic measurements of the stars were taken,” Grün points out. Here, Joseph von Fraunhofer initially began to survey planetary spectra using new and what were then technically advanced instruments. “To this day, this kind of spectral measurement remains the basis of cosmology.” Grün asked three colleagues from other chairs to get together for a talk. The crucial question for these researchers is how the structures of the Universe that we see today could emerge from the initial conditions surrounding the Big Bang.

Puzzles for research

How could the structures of the universe observed today have emerged from the initial conditions of the Big Bang? At the LMU Observatory in Munich Bogenhausen, LMU cosmologists—Sebastian Bocquet, Nils Schöneberg, Rolf-Peter Kudritzki, and Daniel Grün (from left to right)—are discussing this big question.

© Florian Generotzky / LMU

Powerful telescopes

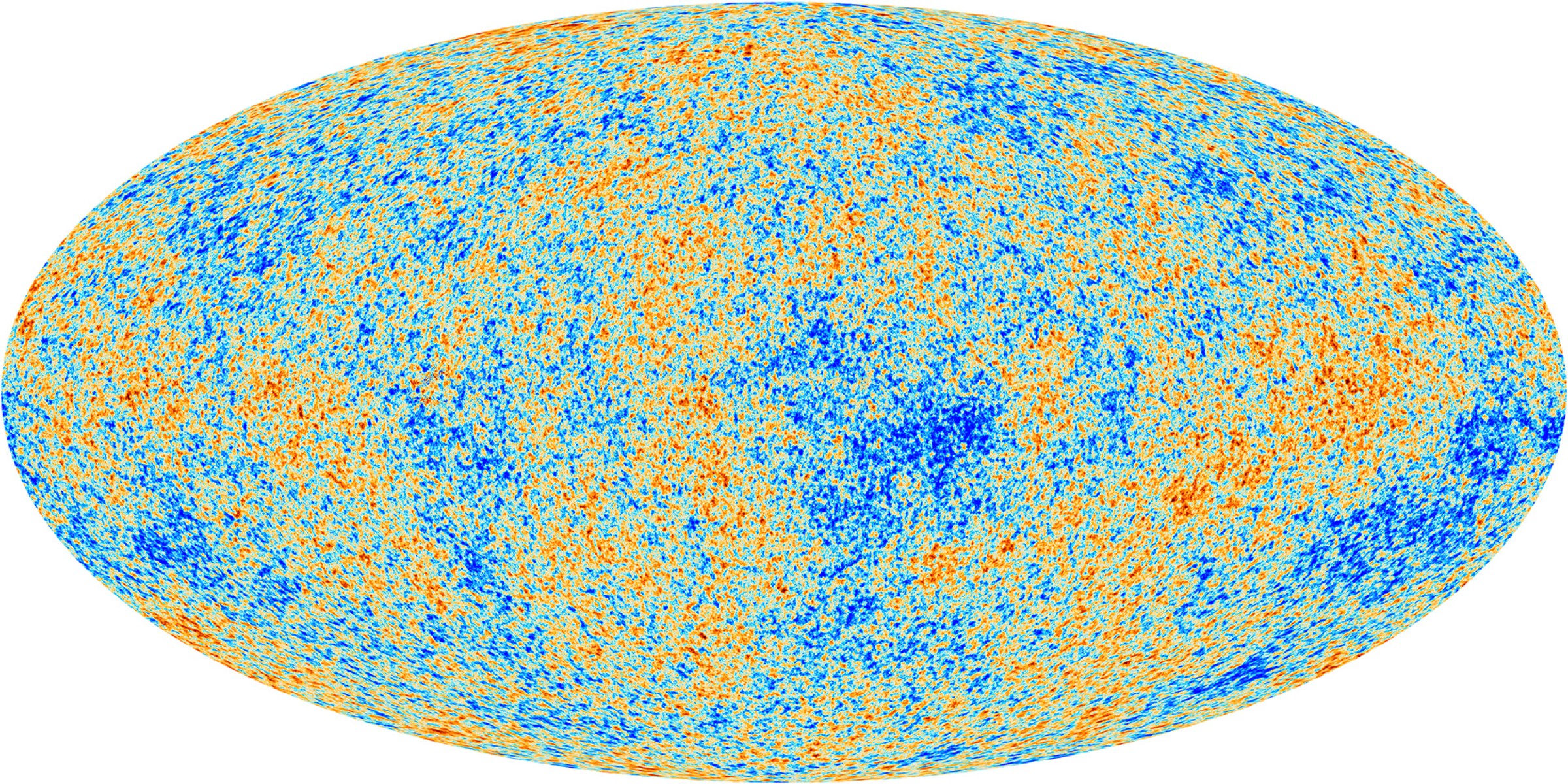

In recent years, powerful telescopes such as the James Webb Space Telescope and the Euclid satellite have begun to measure with increasing accuracy how the Universe is structured today. Possible errors have been reduced, and this places current cosmological discussions on a firmer foundation. Researchers have for some time been able to measure the initial conditions with tremendous accuracy. In 2013, the Planck research satellite delivered a precise image of the cosmic microwave background radiation from a time when the Universe was only 380,000 years old, and had just cooled down enough to become transparent. This radiation contains minute temperature differences that tell us something about how matter and energy were distributed in the early phases of the Universe.

Cosmic microwave background radiation

The Planck research satellite provided a precise image from the time when the universe was only 380,000 years old, was just cooling down, and was becoming transparent. This radiation contains tiny temperature differences.

© Planck / ESA

“The Standard Model links these early stages with the Universe we see today,” Grün explains. Yet this is precisely where certain problems lie: “We see the image of an embryonic Universe and cannot fully explain how this embryo grew into the mature Universe we see today,” he continues. “The model no longer fits quite so well. So, maybe there is a new, unknown physics behind it all.”

The Universe – Like a yeast bun with raisins

One major conundrum relates to the speed at which the Universe is currently expanding. In physics, this is the fundamental parameter when it comes to understanding the Universe. It can be measured directly if, at the same time, you can determine the distance of a galaxy and the speed at which it appears to be moving away from us. Seen from the Earth, the Universe can be imagined like a kind of yeast bun with raisins: When the dough rises, all the raisins (or galaxies) move away from each other at a speed that is proportional to their distance from each other.

Cosmologists have only known that the Universe is expanding for just under 100 years. Astronomers such as Georges Lemaître and Edwin Hubble formulated the theory, and Hubble introduced the constant that was named after him to describe the current rate of expansion. The problem is that different measurements of the Hubble constant arrive at differing values: Researchers refer to this phenomenon as the “Hubble tension”.

Keeping an eye on the big picture

“We see the image of an embryonic Universe and cannot fully explain how this embryo grew into the mature Universe we see today,” he continues. “The model no longer fits quite so well. So, maybe there is a new, unknown physics behind it all.”

© Florian Generotzky / LMU

How to develop a cosmic ruler

The key question is therefore: Where does this discrepancy between values come from? Is the problem rooted in the measurements, or in the theory? Answering this question is not easy, because measuring cosmological distances is complicated. For a long time, researchers therefore assumed that their measurements might be wrong. The most difficult method involves measuring the distance to other galaxies. To do so, you have to develop a kind of cosmic ruler, a distance ladder along which you can slowly climb to ever greater distances. You first determine the distance to nearby galaxies before then taking gradual steps toward the next class of distance indicators known as supernovae, as Rolf-Peter Kudritzki explains. Kudritzki, the former director of the LMU Observatory, spent many years conducting research using telescopes in Hawaii and is now back working at LMU again.

What was long regarded as the best method used bright, variable stars that can be detected individually in nearby galaxies if you use a large telescope. Researchers often refer to these Cepheids as “standard candles” in the Universe, because they provide orientation along the cosmic ruler. One typical attribute of these stars is that their brightness varies; and the duration or period of these fluctuations is linked to their absolute brightness. And since a period can be measured quite well, along with its apparent brightness, it is possible to draw conclusions about the distance of the galaxy a Cepheid is situated in.

Researchers long remained in the dark about whether systematic measuring errors were happening. “The Cepheid method does have weaknesses,” Kudritzki concedes. For example, the fluctuation period depends on the chemical composition of these stars. This, however, cannot be determined directly for stars in distant galaxies, because they are not bright enough for their spectra to be observed. A second weakness is that the space between stars in the galaxy is not completely empty, so part of their light is absorbed.

Innovative method

LMU cosmologist Rolf-Peter Kudritzki used the spectra of the brightest stars to determine the distance to distant galaxies such as Messier 101, shown here. The image was taken by the Hubble Space Telescope.

© Hubble / ESA

Development of a new distance measurement

Kudritzki therefore developed a new method of measuring distance, using detailed spectroscopic measurements of the brightest stars there are: “blue supergiants” – stars with 30 to 40 solar masses that are up to a million times brighter than our sun. Kudritzki notes that both the spectra and the chemical composition of these stars, which are found even in very distant galaxies, can now be determined very well using large telescopes. “However,” he adds, “developing a suitable method wasn’t easy. We worked our way from neighboring galaxies such as the Magellanic Clouds to galaxies that are further away. That cost my working group 50 years of work.” The method has now become established. And the important thing is that it gives Kudritzki a measurement of distance to nearby galaxies that is consistent with the Cepheid method. “There are no more serious measuring errors,” he says.

Direct measurements of the Hubble constant thus deliver stable expansion rates of around 74 km/s/Mpc (equivalent to 3.26 million light years). On the other hand, the figure derived from background radiation is only 67.4 – a value for which having the correct theory is very important though. All of which makes a clear statement: There is a fundamental problem with the theory.

In principle, that is “business as usual” in the science world: You formulate a new theory as soon as your experiments are sufficiently accurate that discrepancies can no longer be explained away by measuring errors. “It was no different for Johannes Kepler when measurements showed that the planets trace not circular but elliptical orbits around the sun,” Grün says. The Standard Model already had to be corrected 25 years ago when it was discovered that the Universe has recently been expanding ever faster. For this finding, astronomers Saul Perlmutter, Adam Riess, and Brian P. Schmidt were awarded the Nobel Prize. After measuring the brightness of distant supernovae, they concluded that the rate of cosmic expansion was accelerating.

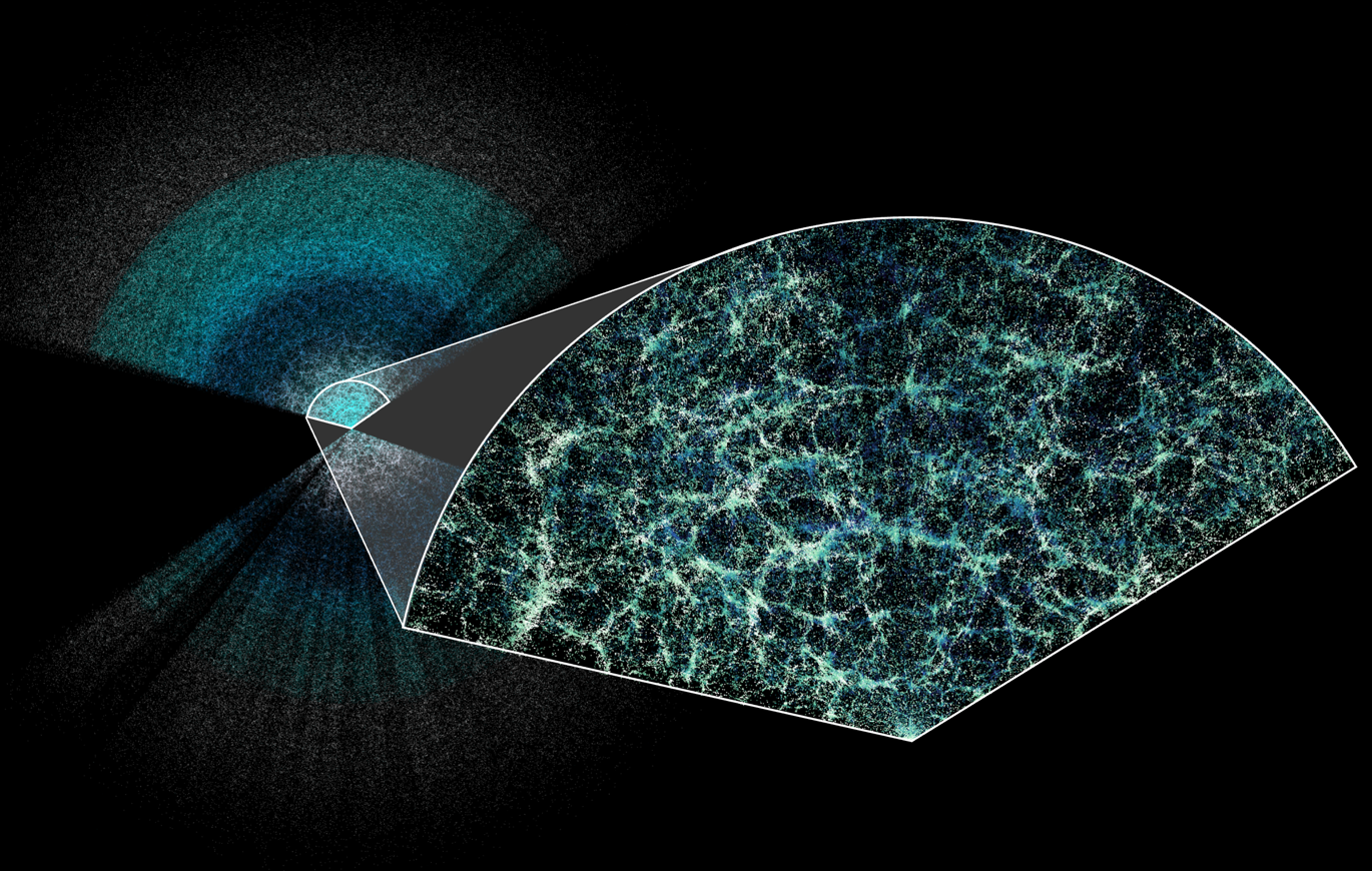

Measuring the universe

DESI has made the largest 3D map of our universe to date. Earth is at the center of this thin slice of the full map. In the magnified section, it is easy to see the underlying structure of matter in our universe.

© Claire Lamman/DESI collaboration

So, the model isn’t perfect?

This and other discoveries prompted researchers to add dark energy and dark matter to the models, although nothing is yet known of their nature. Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity predicts such accelerated expansion if a universe comprises a good mix of normal matter and a “dark energy” that fills empty space at all times with the same volume of energy per cubic meter. Back then, the Standard Model was broadened into what became known as the Lambda CDM model, which includes the vacuum energy lambda (Λ) and cold dark matter (CDM). “Until ten years ago, this appeared to be the perfect construct with which to understand the Universe,” Grün notes. Yet here again, there is a problem relating to more accurate Hubble constant measurements.

LMU researchers are currently contributing valuable insights to this question, especially thanks to their involvement with the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI) at the Kitt Peak National Observatory in the US state of Arizona. DESI’s purpose is to perform spectroscopic surveys of far distant galaxies. This enables researchers to track the expansion history of the Universe more exactly than ever before by determining distances and apparent recession velocities with the aid of what are now more than 50 million galaxies.

In this way, DESI measures the change in the expansion of the Universe over the past ten billion years – and encounters a problem: “It looks as if the expansion of the Universe does not accelerate at the constant rate that vacuum energy would cause,” says Nils Schöneberg, Fraunhofer-Schwarzschild Fellow at LMU. Instead, the influence of “dark energy” seems to have dropped off unexpectedly over the past five billion years.

»It’s as if dark energy were literally turning to dust. But we have no idea how. There is no theory that even begins to tackle this issue.«

Daniel Grün

Does dark energy turn to dust?

Clearly, mysterious things are happening in the Universe. “It’s as if dark energy were literally turning to dust,” in Grün’s words. “But we have no idea how. There is no theory that even begins to tackle this issue.”

Schöneberg is evidently not convinced by the notion that dark energy turns to dust, i.e. that it becomes matter. He thinks that it could also simply disappear, or that we have so far still been drawing incorrect conclusions from the cosmic microwave background radiation. The physicists thus launch into a lively discussion on the behavior of cosmic vacuum energy, acoustic waves from the early days of the Universe and how the latter might be used as a sort of cosmic ruler. Sebastian Bocquet, an LMU scientist at the ORIGINS Excellence Cluster, says that it is always like this in the weekly discussions whenever new papers are presented.

Counting galaxie from the South Pole

Data from the South Pole Telescope (pictured) help to map the large-scale distribution of galaxies in the universe.

© Geoffrey Chen

In search of a new physics

According to Bocquet, who specializes in analyzing large data sets at LMU, it seems that some apparently huge discussions can indeed be resolved in this way. How do we know? Well, until recently, there was a third gaping crack in the foundations – known as “S8 tension” – that, however, has since been mended. The S8 parameter is an indicator of the extent to which the density of matter fluctuates from one place to another. For roughly a decade, a technique known as gravitational lensing seemed to show that S8 had a lower value than had been expected from the cosmic microwave background radiation.

More recent papers, including one from Grün’s former doctoral researcher Jamie McCullough, highlight effects that explain part of the lower values and could therefore reduce the error. Now, Bocquet’s new analyses based on data from the South Pole Telescope and the Dark Energy Survey prove that the values actually do match. To arrive at this finding, Bocquet assessed the distribution of galaxy clusters in the Universe as a measure of how homogeneously mass is distributed. The S8 value he obtained is only slightly below the value from the cosmic microwave background. It therefore seems that the structural distribution of today’s Universe and that of the young Universe do indeed fit together within the scope of measurement precision.

The other cracks in the foundations remain unresolved. But the researchers actually seem quite excited about this: What could be better than the search for a new physics?

Prof. Daniel Grün holds the Chair of Astrophysics, Cosmology, and Artificial Intelligence at LMU. Prof. Rolf-Peter Kudritzki is a professor of astrophysics, former director of the LMU Observatory, and currently director of the MIAPbP Center (Munich Institute for Astro-, Particle and BioPhysics) at LMU. Dr. Nils Schöneberg is a Fraunhofer–Schwarzschild Fellow at LMU. Dr. Sebastian Bocquet is an Academic Councilor at LMU, and completed his habilitation in astrophysics in 2025.

All four LMU astrophysicists are members of the ORIGINS Cluster of Excellence.

More rethinking in this issue:

Read more articles from LMU's research magazine in the online section and never miss an issue by activating the magazine alert!